As I mentioned in my previous blog about Gil Hodges, I grew up in Terre Haute, Indiana. My friends from Terre Haute were fans of the Cubs, White Sox, Cardinals, or Reds. My team was the Cincinnati Reds and Pete Rose was my guy.

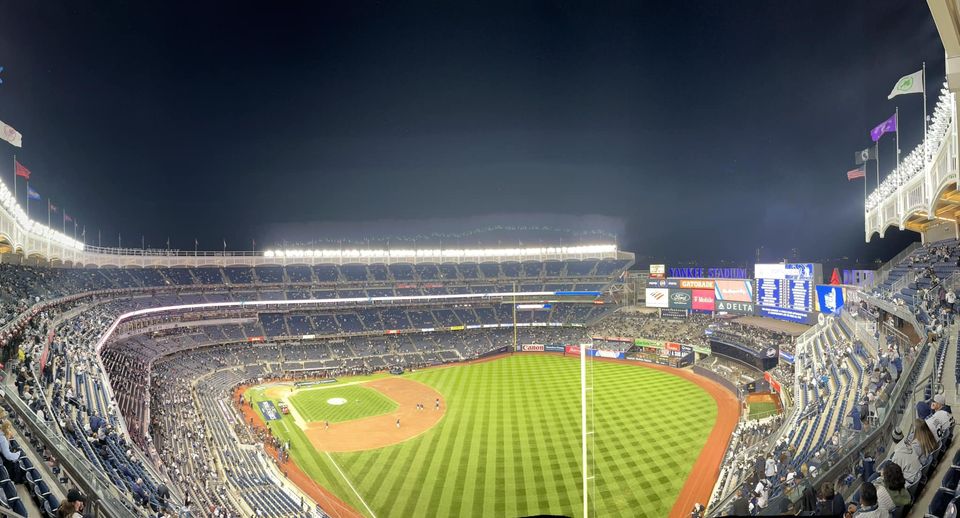

I was born in 1968. Most of my memories of the Reds are from games at Riverfront Stadium, and I saw lots of them. The 1990 wire-to-wire, World Series Champion season was probably the best. Opening days are always special, but there is nothing like post-season baseball on a cool fall day in Cincinnati.

Like most people in Reds Country, I treasure the memories I have of listening to Marty Brenneman and Joe Nuxhall on the Big One, 700 WLW. Marty and Joe were broadcast partners with the Reds for 31 years! The people of Cincinnati love them both so much. Marty was polished and is a Hall of Fame Ford C. Frick Award winner. Not many, if at all, were better than Marty Brenneman. Joe was the hometown guy, the “Ol’ Left-Hander” from nearby Hamilton, Ohio (Hamilton is about 20 minutes north of downtown Cincinnati). Joe had a folksy-style that was uniquely his. Marty called it like he saw it. Joe always pulled for his team. They were great friends on and off the field and a perfect pair in the booth.

I have started working on a project about Joe Nuxhall that I hope to present one day at the National Baseball Hall of Fame’s Cooperstown Symposium on Baseball and American Culture. As part of my research, I recently spent a little time with Chris Eckes of the Reds Hall of Fame Museum and Kim Nuxhall (one of Joe’s sons). Both seemed like great guys and were very nice to me.

This blog is to share a few pictures and stories of my time in Cincinnati learning about Joe Nuxhall.

It is important to remember Joe Nuxhall because Joe is a cultural symbol of community in Cincinnati. The people of Cincinnati have found ways to sprinkle little reminders of him around to help them feel safe. Joe’s legacy reminds us to be humble and care for each other.

Joe grew up in the North End neighborhood of Hamilton and was first scouted by the Reds in 1943 as a 14-year-old. Rosters were depleted during this time of World War II but the Reds still believed in Joe’s talent as a ball player and signed him to a contract. I took the following four pictures at North End Ball Park on September 13, 2025.

After starting the 1945 season in spring training, Joe decided he wanted to return to Hamilton and finish high school. At Hamilton High School, Joe was a star athlete. His favorite sport was basketball. Joe was all-state in basketball and football while at Hamilton High School.

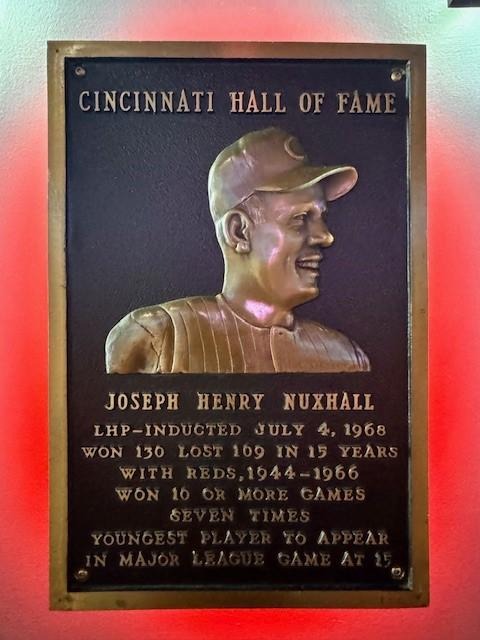

After high school, Joe returned to the Reds. It would take him about 7 years to make it back to the big-league roster. There were highs and lows in Joe’s playing career. The early and mid-1950s were good years for Joe. He won 17 games for the Reds in 1955 and was a two-time all-star (1955 and 1956). The latter part of the decade was not so good. Joe was booed at home games. Fed up, he requested a trade and was dealt to the Kansas City A’s. It was during his couple of years away from Cincinnati that Joe learned a few things. The first thing he learned was how emotions negatively impacted his performance on the mound. The second thing he learned was a good curveball. Joe returned to the Reds and finished his playing career in 1966. When he retired, he was first all-time in strike-outs and appearances for the Reds. Joe was elected to the Reds Hall of Fame on July 4, 1968.

Joe officially retired during spring training in 1967 and immediately joined Claude Sullivan and Jim McIntyre in the radio booth for the Reds. After later working with Al Michaels for three years, Joe was joined by Marty Brenneman in the radio booth at the beginning of the 1974 season. The magic that Marty and Joe had was special. Marty respected the player Joe was and understood what Joe meant to the people of Cincinnati. There are lots of calls and tv commercials and pictures to help tell the story about Joe and Marty’s time while working with the Reds. I can still watch and listen to that stuff all day.

The next three pictures are from the Marty and Joe Broadcast Exhibit in the Reds Hall of Fame. Joe and Marty’s last microphones are on display in the Exhibit. The fourth picture is one I like of Marty and Joe having a good time at Riverfront Stadium. Those guys really had fun.

If you have are in Cincinnati, the Reds HOF Museum is a must-see!!

Joe would have been remembered for his time on the field, but it is what he did after his playing career was over that means the most to the people of Cincinnati.

Joe was always around. He hated to turn down an invitation to support anything. Little League games. Speaking at banquets. Joe was very approachable and very humble. The people of Cincinnati relate to his genuineness and appreciate the love he showed for his hometown.

Perhaps the most impactful thing that Joe did was form the Joe Nuxhall Foundation. The Joe Nuxhall Foundation funds the Joe Nuxhall Memorial Scholarships, Joe Nuxhall Character Education Fund, and the Joe Nuxhall Miracle League Fields.

Joe Nuxhall Memorial Scholarships are presented to high school seniors in Butler County each year. Next year, in 2026, the Joe Nuxhall Memorial Scholarships will cross over the $1 million mark for total awards.

Character development was very important to Joe. The Joe Nuxhall Character Education Fund was established to underwrite character development and projects for children.

The Joe Nuxhall Miracle League Fields are in Fairfield, Ohio. Kim Nuxhall runs the Miracle Fields. It was a dream of Joe’s to see children and adults with disabilities playing the game he loved so much. There are two diamonds with electronic scoreboards and lights. Kids and adults join teams and play in leagues. The day I was there, I watched the Giants play the Angels. The kids had a great time. I saw a kid do the moonwalk as he walked to home plate to bat, and I watched a young girl using a walker get two hits as the announcer told everyone it was her birthday.

When I visited the Joe Nuxhall Miracle League Fields (on August 30, 2025), Kim Nuxhall told me about a new major project he’s very excited about (www.nuxhallmiracleleague.org/hope). Kim told me they are currently planning and fundraising to construct a new “Joe Nuxhall Hope Center” on the Miracle League Fields property. If I remember right, the cost will be about $12 million. The new Hope Center will be a 31,000 sq. ft., inclusive, indoor recreation center. With the addition of the new Hope Center, the Joe Nuxhall Miracle League Fields will be the world’s most inclusive, comprehensive campus for athletes and individuals with exceptionalities.

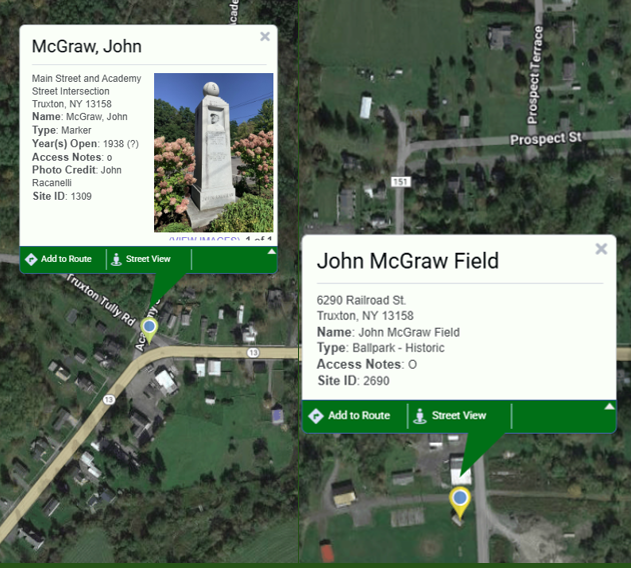

Joe is remembered inside and outside of Great American Ball Park. The street address for Great American Ball Park was changed to 100 Joe Nuxhall Way. Streets in Cincinnati, Farfield, and Hamilton are named after Joe. Player awards are named after Joe. A summer collegiate league team is named after Joe. College baseball teams in Cincinnati play in the Joe Nuxhall Classic.

Conclusion

“Rounding Third and Headed for Home”. Joe used that phrase as his sign-off each night following his post-game wrap up on the radio. He’d conclude each show by saying “This is the ol’ left-hander, rounding third and headed for home”. That phrase became associated with Joe Nuxhall. I think it has sort of a poetic meaning particularly because of the word “HOME.” The people of Cincinnati associated Joe Nuxhall with “HOME.” Home is a safe place where you can relax and be with family. “Hamilton Joe” represented “HOME” to the people of Cincinnati.

Joe Nuxhall was like a special tree or park or garden that a community treasures and celebrates around. Even 18 years after his death, the people of Cincinnati hold memories of Joe close to their hearts.

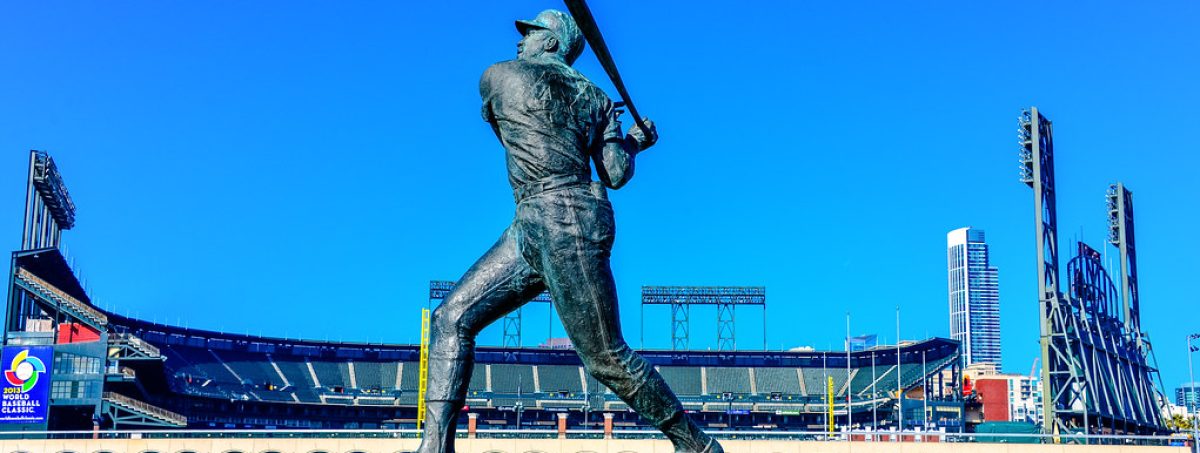

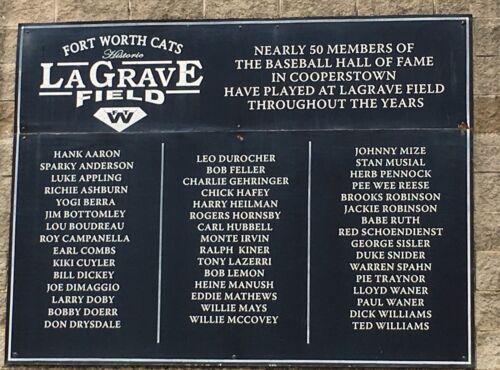

Marty Brenneman is quoted as saying that Joe is the most popular figure in the history of the Cincinnati Reds. That’s high praise considering that six of the nine bronze statues on Crosley Terrace outside Great American Ball Park are members of the National Baseball Hall of Fame…. and Joe Nuxhall isn’t one of them!

During our tour of the Reds HOF Museum, Chris Eckes commented that the people of Cincinnati grab hold of their hometown heroes with both hands and don’t ever let go.

The people of Cincinnati are holding tightly to the memory of Joe Nuxhall. Thank you Joe.

I hope you enjoyed seeing the pictures and reading my blog about Joe Nuxhall. Maybe I’ll finish the project and get to present it one day at Cooperstown?!?!

Additional Comments

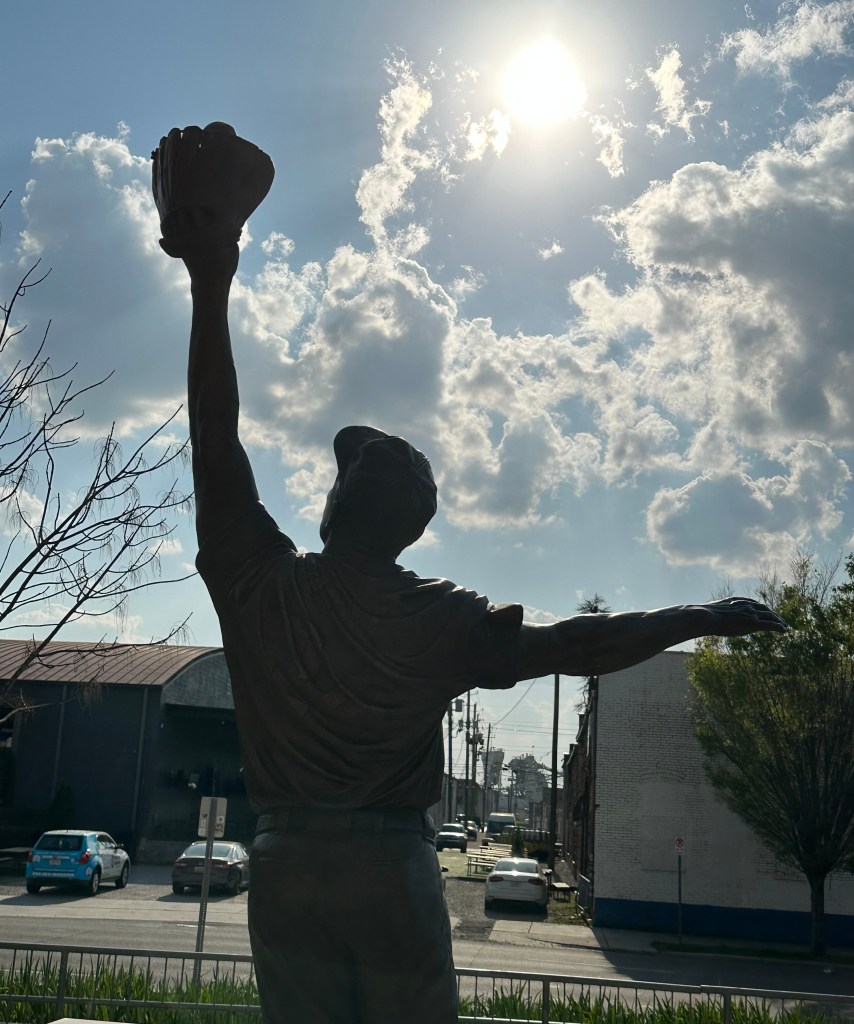

Marty Brenneman’s statue at Great American Ball Park was unveiled on September 6, 2025. A very large crowd came out to thank and celebrate Marty that day. I took these pictures from “way in the back”. Congrats Marty. You, too, are in a league by yourself.