Amid the noise of bouncing basketballs and splashing in the new pool at the Athletic Recreation Center, there exists a baseball diamond whose provenance is embedded in baseball’s past. Just outside the fence along the third baseline stands a Pennsylvania historical marker that details that background. Primarily funded by the generous donations of SABR members and dedicated in September 2017, the marker explains that the property played host to the first National League game, was the site of the first interracial baseball game and was home of the American Association’s Philadelphia Athletics.

In 2015 I went down a rabbit hole and discovered Jerry Casway’s biography of the Jefferson Street Ballparks. I was new to SABR and just developing my passion for 19th century baseball history. After learning about the extraordinary history that took place there, I decided to hop in my car and make the half hour trek to the Athletic Recreation Center and view the site with my own eyes. When I arrived, I walked onto the field where I was mentally transported back in time. I tried to imagine the sights, sounds and smells that would have been familiar to those who visited the ballparks during the 19th century. I’d like to take you on that journey.

The Jefferson Street ballparks were situated in a Philadelphia neighborhood called Brewerytown. Its proximity near the Schuylkill River, outlying farms, and lack of development attracted brewers and beer related industries to the area in the 1860s. The Philadelphia Evening Bulletin recalled the Brewerytown of the late 19th century with fondness. “…the air was as nourishing as vaporized bread…It was a place for family bakeries and rich delicatessens, a neighborhood scrubbed to within an inch of its life and resounding to the guttural language of Goethe and Schiller…” Railroad lines serviced the industry along the river while streetcar lines acted as the neighborhood’s public transit option, bringing fans to and from the ball grounds. The noises and smells of a developing Brewerytown enveloped this epicenter of Philadelphia baseball for nearly three decades.

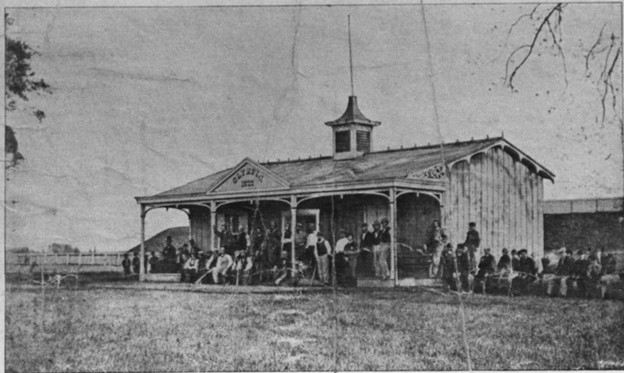

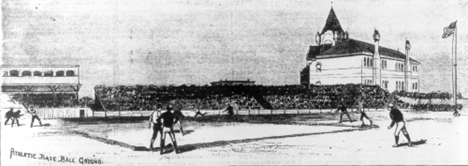

The property was used regularly for baseball beginning in 1864 when the Olympic Ball Club leased the grounds. On September 3, 1869, the first interracial baseball match between nationally prominent clubs was played at the Jefferson Street Grounds. The Olympic Ball Club, an all-white team, and Philadelphia Pythians, an all-black team, squared off in a match that was reported on as far away as Utah.

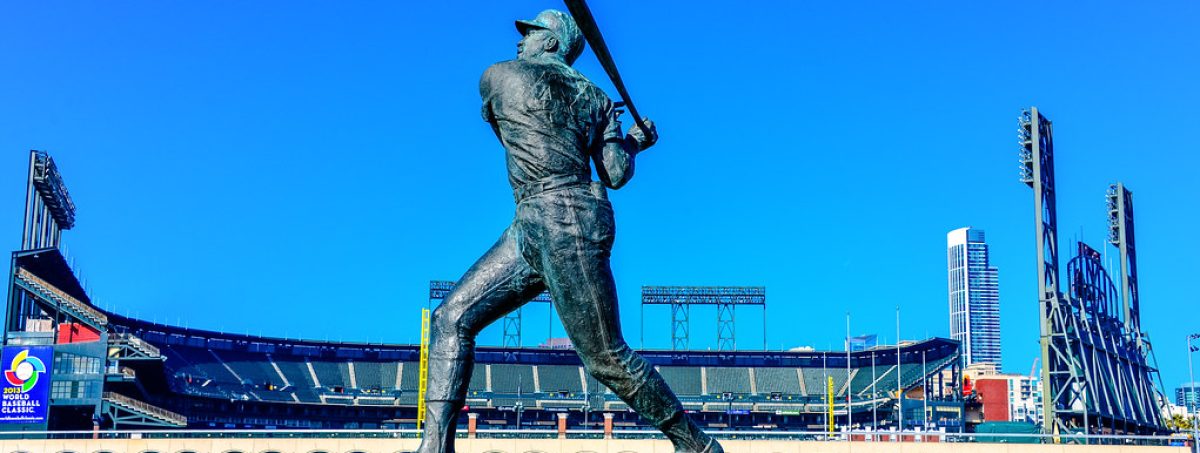

The Athletics called Jefferson Street home during their championship season of 1871, the first professional baseball league championship season in history. On April 22, 1876, all the inaugural National League games were rained out except the game in Philadelphia where Boston defeated the Athletics in the first National League game in history. But the Athletics were expelled from the League at the end of the season, ending Philadelphia’s affair with top-flight baseball. It would be six years before Major League Baseball returned to the Quaker City and Jefferson Street.

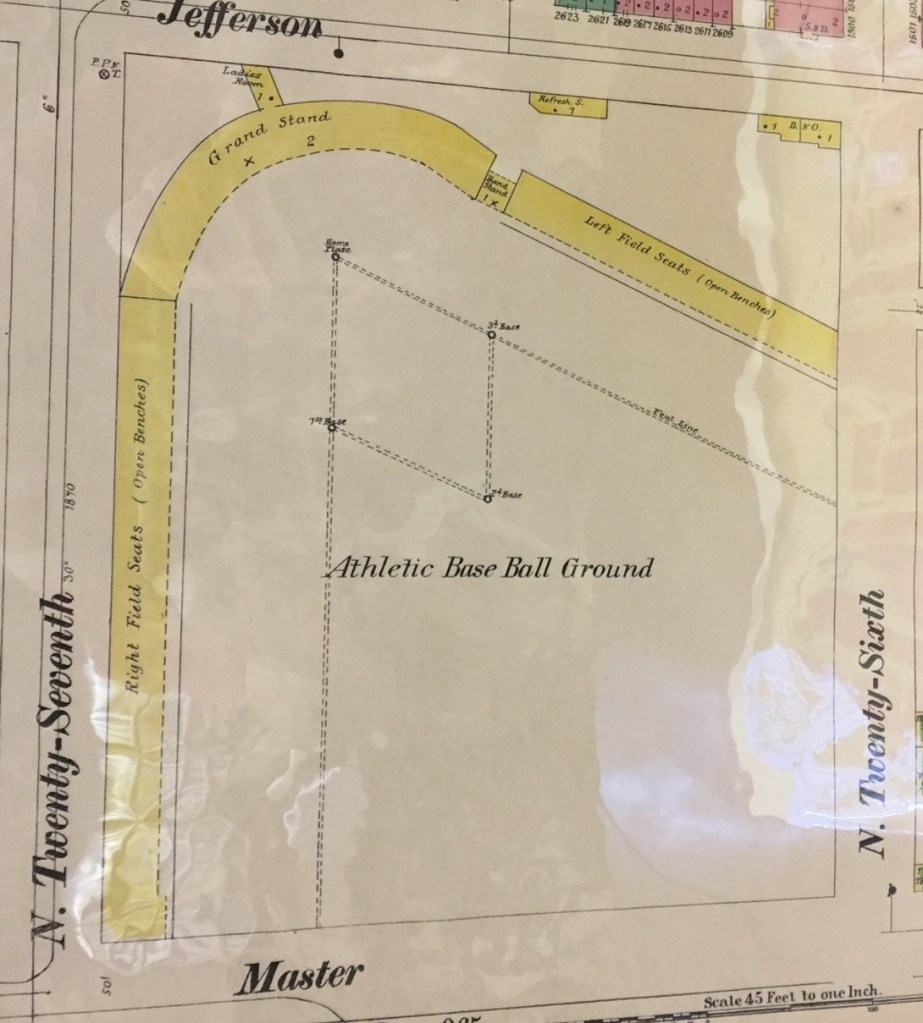

The Jefferson Street Grounds experienced change in the absence of top-flight baseball between 1877-1881. A school was constructed on the original field, while 26th street was cut through the middle of the lot. But in 1883, baseball returned to Jefferson Street when the American Association’s Philadelphia Athletics constructed Athletic Park at 27th and Jefferson streets. The first city championship game in years was played on April 14 between the Athletics and Al Reach’s Philadelphia Phillies. The account published in the Times noted that “the audience gave audible criticisms on the merits of both nines” when the squads were warming up on the field. Evidently, Philadelphia fans haven’t changed in 139 years. Toledo visited Athletic Park on May 26, 1884, and when Moses Fleetwood Walker, MLB’s first African American player, stepped to the plate for the first time, the Philadelphia fans rose to their feet and applauded him. Jackie Robinson received a different reception 63 years later.

I thought about these things as I stood in the baseball diamond at the Athletic Recreation Center. I could almost smell the beer, hear the fans yelling themselves hoarse, and see Moses Fleetwood Walker step into the batter’s box as the American flag lazily waved in deep center field. History buries its treasure deep.

In the case of the smells, sounds, and sights from within the Jefferson Street ballparks our imagination is almost all we have that will allow us to visit this space as it once was. Newspaper accounts the only vestiges of their existence. But they are lacking the context that I often enjoy, the fan experience. I left the Athletic Recreation Center convinced that I needed to do something to memorialize the place and the people who made it important.

Finding what made the Jefferson Street ballparks special and worthy of a Pennsylvania State Historical Marker wasn’t difficult. Period newspaper accounts and images combined with secondary source work made this nomination a home run. I was confident the oversight committee would approve the marker. My concern was funding the marker.

The cost for the historical marker in 2017 was approximately $2,000. I had created a GoFundMe in late 2016 to fundraise and by late March, had raised approximately $500 of the $2,000. On March 27, 2017 I announced that the Pennsylvania State Historical and Museum Commission (PSHMC) approved my nomination. Once this announcement was made, full funding was achieved within a week!

The next challenge was finalizing the wording with the PSHMC. Ultimately everything I wrote made it onto the sign with one alteration: I stated that the April 22, 1876, game between Boston and the Athletics was the first Major League Baseball game in history. Despite explaining that MLB has held that stance since 1969, the PSHMC required the wording to be changed to “first National League game.”

The Jefferson Street Ballparks historical marker was officially dedicated on September 30, 2017. Speeches were given by Dick Rosen, then Co-Chair of the Connie Mack SABR chapter, Rob Holiday, Director of Amateur Scouting Admin of the Phillies, a member of the Athletic Base Ball Club of Philadelphia (vintage baseball), and me. After the speeches and the unveiling, the Athletic Base Ball Club played a game of Philadelphia Town Ball and invited attendees and those in the community to join in the action. The Athletic club’s uniforms are almost exact replicas of the Athletics’ 1866 uniforms. It was surreal seeing those uniforms back on such a historic field. My favorite part was the young kids engaging in a 19th century game on a field where so much history had taken place, and their naivete to it all. The Philadelphia Inquirer covered the event and published a story in their October 1, 2017, issue

Just days ago, the Philadelphia faithful packed Citizens Bank Park three straight nights as the Phillies hosted the Houston Astros in the 2022 World Series. It has been an exhilarating month for Philadelphia baseball fans, who have once again become a topic in the grand postseason narrative. I had the privilege to attend two postseason games, both Phillies victories, and they were both the loudest baseball experiences I’ve ever had. The crowd was authentic, bombastic and boorish. As we cheered our Phillies and jeered the opposition, the wind rustled leaves on an old crusty baseball diamond in Brewerytown, some five miles away from Philadelphia’s current baseball epicenter. Did our voices travel those five miles to Jefferson Street and transform into distant echoes of what once was a hotbed of baseball activity? Maybe that’s too mystical for the real world, but I’ll choose to believe it.