Since the Hardball Voyager blog was announced, I tried to pick a favorite local landmark to write about related to Pittsburgh baseball. I failed, as there are too many “favorites.” So instead, let’s talk “favorite oldest” landmark.

With recent improvements to the outfield concourse (stress on the word “improvements”), PNC Park is even more rife with reminders of the region’s baseball past than previously. Cartoonish bobblehead statues, club hall of fame plaques, and colorful, decorative signage are just some of the welcome additions to the home of a team with such a long (and occasionally) storied history.

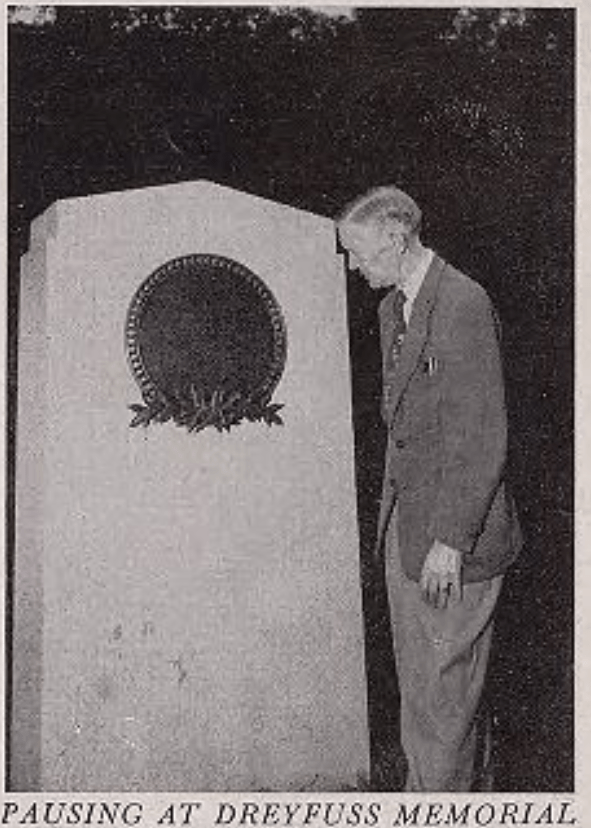

While the new-fangled items are great and welcome, there’s one longtime object within the stadium that has my heart. It has stood steadfast through the years, far away from the glitz and color of PNC’s outfield. Amidst one of the busiest areas in the stadium, it somehow manages to quietly hide in plain sight–it’s the Dreyfuss monument, located at the top of the Peoples Gate escalator, a short distance from the entrance near the Honus Wagner statue. Aesthetically, there is nothing overly significant about the monument itself; a large, gray, tombstone-like slab ornamented with a small, circular bronze plaque. Most folks entering the ballpark probably don’t even notice it, as it seems to fit as a piece of the building’s structure. But given who it is there to memorialize, and given the history it has seen, the marker is a standout amongst so many others on the other side of the ballpark.

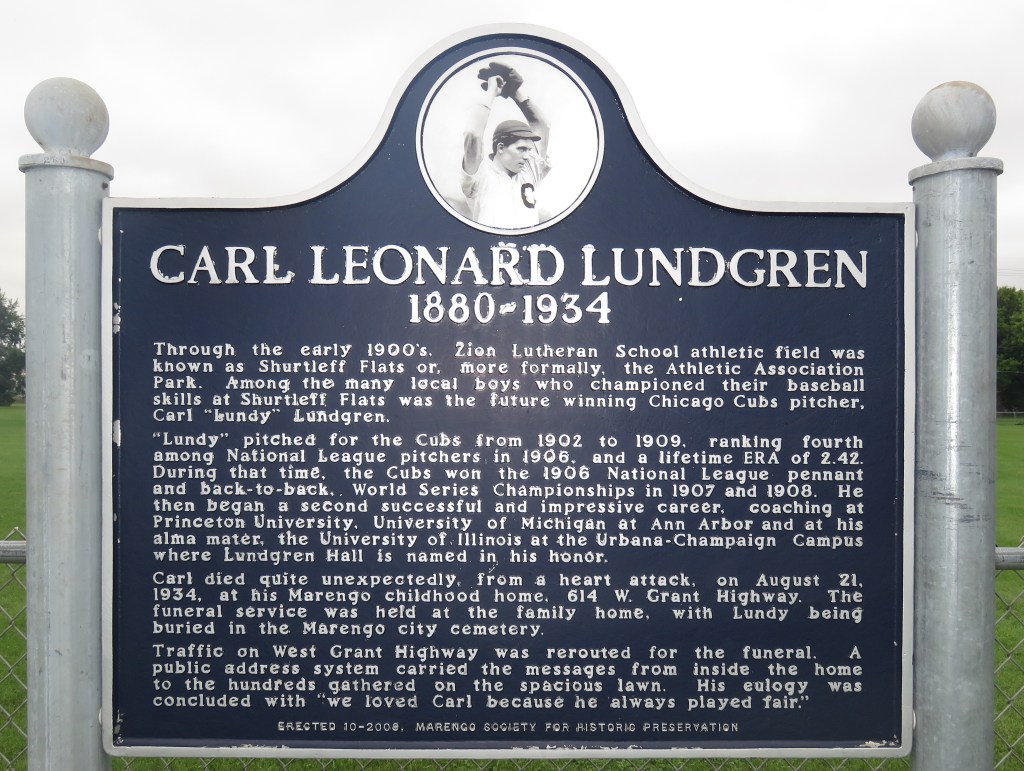

Following nearly two decades of (relative) historical anonymity, the Pittsburgh National League team really burst onto the national baseball scene in 1900. Barney Dreyfuss bought into and (essentially) merged the franchise with the soon-to-be retracted Louisville club, a team he’d previously owned. The combination of the Pittsburgh team with a number of players from Louisville (the previously mentioned Wagner included) turned the new club into a powerhouse in the NL standings immediately, and the success continued for the next decade.

Even though the shine faded a bit after 1912, Dreyfuss’s organization managed to rebound a few years later, and what followed was another period of strong finishes throughout the 1920s. Barney’s knack for finding the right people (both player-wise and management-wise) was evident from looking at the results during his stewardship; the team landed in the upper echelon of the NL quite a bit. They captured six pennants and finished as either runner-up or third place seven times each.

As Dreyfuss aged, his intention was to pass ownership of the Pirates on to his son, Samuel. The younger Dreyfuss joined the club in 1920, and apprenticed as the team’s treasurer, as well as taking numerous other roles in the employ of his father during the Pirates’ resurgence. Unfortunately, tragedy struck in 1931 when Samuel passed away from pneumonia at the age of 34. It has been theorized that the loss of his son was the psychological and emotional blow that led to Barney’s decline and death only a year later.

Two and a half years after Barney Dreyfuss passed away, a monument dedicated to both Barney and Samuel was unveiled at the game that marked the 25th anniversary of one of Barney’s crowning achievements—the opening of Forbes Field. NL president John Heydler and several local dignitaries were on hand for the ceremony. The memorial for the Dreyfuss men was placed in deep centerfield, near the flagpole. In the years following, the monument saw a good bit of action, as it was located within the field of play. Just like the early years of Yankee Stadium’s Monument Park, outfielders had to be aware of their surroundings, lest they become part of an unwanted collision.

After the Pirates moved in the early 1970s, the Dreyfuss monument was as well, transported from the Forbes outfield to a more fan-friendly (and less hazardous) concourse location in Three Rivers Stadium. In 2001, it was taken to the new digs on the concourse at PNC Park, and resides there to this day.

If you come to a game in Pittsburgh, it’s imperative that you take in the statues and various markers celebrating the players and history of the Pittsburgh Pirates. Above all others, though, I ask that you be certain to stop by the simple gray slab, near the home plate entrance, to pay your respects to the two Dreyfuss men who left an indelible mark on Pittsburgh baseball history.